Cant Explain Next Few Months Phenomenomenom Again

By Jared Bernstein and Ernie Tedeschi

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused an anarchistic recession, and we do not expect the recovery will be typical either. While the paramount policy goals are to control the virus, get to full employment, and brand the necessary investments for a more resilient and inclusive recovery, economic uncertainties and risks demand conscientious attention going forward. One gamble the Assistants is monitoring closely is aggrandizement.

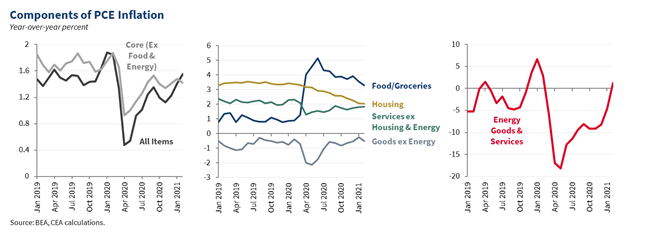

Inflation—or the charge per unit of change in prices over fourth dimension—is not a unproblematic phenomenon to measure or interpret. Inflation that is persistently too high can hurt the wellbeing of households, peculiarly when it is not offset by comparable increases in wages, leading to reduced buying ability. But aggrandizement that is persistently too low leaves monetary policy with less scope to support the economy and tin can be a sign the economy is beneath its chapters, thus with room to expand jobs further. Indeed, 1 piece of important context around the current inflation risks is that inflation was generally weaker than the Federal Reserve'south target over the decade prior to the pandemic as the economic system recovered from the Great Recession. Overall inflation, as defined past the Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) deflator, then vicious further during the pandemic, though there have been important differences between products and sectors (see figures below).

Pandemics of the magnitude of COVID-19 are, thankfully, rare, just that also means few historical parallels be to inform policymakers. The United states experienced brusk bursts of inflation in some prior periods of pandemics or big-calibration reallocations of economic resources, such as in 1918—driven by the Castilian Flu and demobilization from World War I—as well as the demobilization from Earth State of war II after 1945 and the resurgence in defence spending due to the Korean War. But history is not a perfect guide here. The 1957 pandemic, for example, which coincided with a nine-month recession, saw inflation weaken, with no large resurgence even when the pandemic was over and the economic system was growing again.

That said, in the next several months we expect measured inflation to increase somewhat, primarily due to three dissimilar temporary factors: base effects, supply chain disruptions, and pent-upwards demand, particularly for services. Nosotros wait these three factors will likely be transitory, and that their impact should fade over time equally the economic system recovers from the pandemic. Subsequently that, the longer-term trajectory of inflation is in big role a function of inflationary expectations. Here, too, we run across some increase, merely from historically low to more than normal levels. We explain our reasoning below.

Base Effects

In the near-term, we and other analysts expect to see "base-effects" in annual inflation measures. Such furnishings occur when the base of operations, or initial month, of a growth rate is unusually depression or high. Betwixt Feb and April 2020, when the pandemic was taking hold in the economy, the level of average prices—as measured by the cadre PCE deflator—fell 0.five percent, before beginning to rise over again in May (cadre PCE inflation leaves out volatile food and energy prices and thus provides a clearer indicate of inflation; however, the same base furnishings are expected to occur in most price series). This unusually large price decrease early on in the pandemic made April 2020 a low base.

Twelve months later, due to the suddenness and scale of this earlier decline, nosotros expect year-over-yr inflation growth rates for the side by side few months to be temporarily distorted past these sorts of base effects. While nosotros do not withal accept price information for March or April, if we assume monthly inflation going forward stays at a rate of just nether 0.2 percent—the equivalent of a 2 percent annual charge per unit, in line with the Federal Reserve's target—inflation in April and May 2021, measured every bit the percentage change in core PCE prices over the previous year, would attain ii.three percent due to this base of operations upshot. Non only is that rate higher than recent aggrandizement growth rates, it would correspond a sharp acceleration over current cadre price growth rates, such as 1.four percent in Feb of this yr. This broad pattern volition exist nowadays across different cost measures this jump, including the Consumer Price Index (CPI) and Producer Price Index.

The issue with base effects is not that they make inflation measures wrong; the two.3 percentage year-over-year inflation calculation in our illustrative case would still be correct. Rather, the base furnishings distort our understanding of how underlying, well-nigh-term trend aggrandizement is behaving right now, suggesting, for example, higher rates of inflation than most analysts expect to persist. Over the next few months, as the base effects' months drift farther into the past, this distortionary characteristic of the price data should fade.

Supply Chain Disruptions & Misalignments

A second potential source of inflation stems from increases in the cost of product. If the toll of the materials needed to produce a good or service rises (remember of the lumber needed to build a house or the electricity needed to power a factory), a business organisation may pass on these costs to consumers in the form of higher prices; economists call this toll push inflation. In virtually cases, this blazon of inflation is transitory: the price of lumber or free energy rises, but and so stabilizes at a higher level or decreases, with no further touch on on future aggrandizement. This example underscores an important distinction between price levels and inflation, with the latter being the rate at which levels motility upward and down.

We have already seen some supply chain disruptions due to the pandemic. For example, the production of parts for goods like automobiles has been concise at times, especially in factories in Asia that play an increasingly central office in the global supply chain. Transportation and warehousing costs—ground, air, and ocean—take also risen equally cargo logistics have become more difficult. The recent excess in the Suez Canal will add to these issues in the near term. And surges in need for certain products, like those that use computer fries, have caused unanticipated supply constraints in industries such as semiconductors.

While we await global supply bondage to gradually unclog as world economies recover throughout 2021 and across, in the most-term some businesses may temporarily pass on the added costs from these disruptions into higher consumer prices.

Pent-Upward Need, Especially for Services

Finally, prices for many of the services most sensitive to the pandemic— such as hotels, sit-downwards restaurants, and air travel—take decreased due to curtailed demand stemming from consumer anxiety and public health restrictions.

Equally more people get vaccinated throughout the year, however, demand for these and other high-touch services could surge and temporarily outstrip supply. This surge in demand may in role exist fueled by savings many households accumulated during the pandemic, likewise as relief payments from the fiscal responses last year and this year. For instance, Americans may have a loftier demand to eat out in full-service restaurants again afterward this year, merely may notice that there are fewer dining options than were open pre-pandemic. That could prompt restaurants that are still open to raise their prices. And while there are natural limits to how many services we can consume quickly—information technology'due south generally only possible for a family to take one vacation at time, for example—Americans may still try to consume these services more than frequently, or may upgrade to higher-quality versions. Economists call inflation resulting from such surges in spending demand pull aggrandizement.

Again, we wait this to primarily exist a brusk-term consequence; as businesses that shuttered or substantially reduced their services reopen, supply will increment to meet this pent-upwardly demand. Encouragingly on this indicate, new concern germination has picked up in recent months.

Longer-Term Inflation and Expectations

Over the longer-term, a key determinant of lasting price pressures is inflation expectations. When businesses, for example, expect long-run prices to stay around the Federal Reserve's two percent inflation target, they may exist less likely to adjust prices and wages due to the types of temporary factors discussed before. If, withal, inflationary expectations go untethered from that target, prices may rise in a more lasting manner. This sort of inflationary, or "overheating," spiral might and then lead the key bank to heighten interest rates quickly which then significantly slows the economic system and increases unemployment. Economists refer to this scenario as "a hard landing," so inflationary pressures are risks that must be carefully monitored.

It is equally of import to recognize that economic "heat" does not necessarily equate with overheating. We expect that moving from a shutdown economy to a post-pandemic economy—with demand fueled by pent-up savings, relief funds, and low interest rates—will generate not just somewhat faster actual inflation just higher inflationary expectations too. An increment in inflation expectations from an abnormally depression level is a welcome evolution. Only inflation expectations must be carefully monitored to distinguish between the hotter simply sustainable scenario versus true overheating.

The best fashion to do so is to track diverse metrics of aggrandizement expectations. One example is the corporeality of aggrandizement compensation investors need in the bond marketplace. Over the adjacent 5 years (the 5-year measure shown below), markets are pricing in inflation that is consistent with our expectations of some economic heat in the short-term every bit the economy reopens. Over the longer-term (the 5Y5Y series below, which corresponds to the five-year flow that starts five years from now), investors for the moment are bold inflation that is consistent with recent history too every bit the Federal Reserve'due south target.

Other data tell a similar story. The effigy beneath shows a monthly blended measure that summarizes 22 unlike market- and survey-based measures of long-run inflation expectations, including market rates like those shown above as well as surveys of households and professional forecasters. This composite measure also suggests higher expectations, but the levels of these expectations remain well within historical levels.

The data in the figure are from CEA's analysis based, in role, on Ahn and Fulton (2020), The Fed – Index of Common Aggrandizement Expectations (federalreserve.gov).

Conclusions

We think the likeliest outlook over the next several months is for aggrandizement to rise modestly due to the three temporary factors we discuss above, and to fade back to a lower stride thereafter as bodily aggrandizement begins to run more in line with longer-run expectations. Such a transitory rising in inflation would be consistent with some prior episodes in American history coming out of a pandemic or when the labor market has rapidly shifted, such as demobilization from wars. We will, however, advisedly monitor both actual price changes and inflation expectations for any signs of unexpected price pressures that might ascend as America leaves the pandemic backside and enters the next economic expansion.

Source: https://www.whitehouse.gov/cea/written-materials/2021/04/12/pandemic-prices-assessing-inflation-in-the-months-and-years-ahead/

Post a Comment for "Cant Explain Next Few Months Phenomenomenom Again"